Bryan Hiott uses 19th century photographic processes in art.

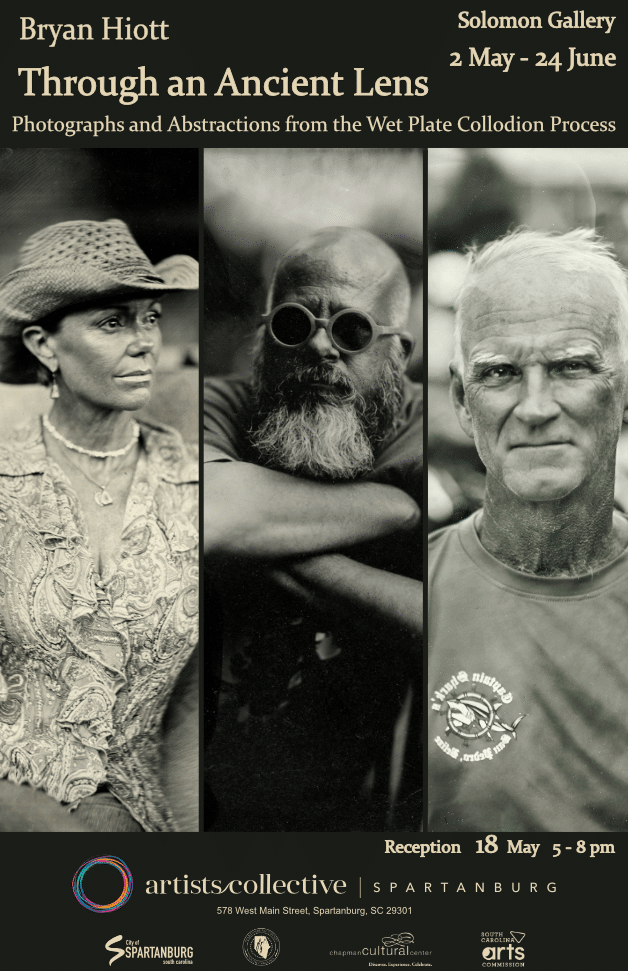

Upstate photographer and artist Bryan Hiott says his upcoming exhibition, “Through an Ancient Lens: Photographs and Abstractions from the Wet Plate Collodion Process,” is a “dialogue” between the rendered photographic images and the materials of the medium he uses. The exhibition will be May 2 through June 24 in the Solomon Gallery of the Artist Collective | Spartanburg.

A reception will be held Thursday, May 18, as part of ArtWalk Spartanburg and an artist’s talk will be held Thursday, June 15.

“The images in this exhibition explore the beautiful tonality of wet plate collodion photography as well as the accidents that may occur with this chemical process,” says Hiott, a graduate of Wofford College in Spartanburg who also received an MFA in photography and digital media from Parsons School of Design. “Certain images display surface imperfections that nonetheless become interesting aspects of the collodion aesthetic. These images, bearing evidence of physical handling, are unique and cannot be repeated.”

Hiott says another facet of the exhibition is the inclusion of “abstract images that are a function of the chemical reactions inherent in the medium. As I examine these reactions on the plates, I carefully consider how they might be composed and presented. I scan them at high resolution and print them at a large scale on paper and on canvas so that the minute details, which include fractals, may be made visible. My exhibition is a dialogue between the rendered images and the materials of the medium.”

Visitors to the exhibition should leave with a greater understanding of 19th century photographic processes, he adds. “I hope that photographers viewing the exhibition might be inspired to try those processes as well.”

Hiott says that while most photography today is digital, he is “captivated by the beautiful tones of the wet plate collodion process, which was invented in 1851 by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer. It was the commercial successor to the Daguerreotype and became the most widely used form of photography in the world through the 1880s. In addition to glass plate negatives, from which paper prints could be made, collodion photography also gave us ambrotypes – positive images on glass – in 1854 and tintypes – positive images on pressed iron sheets – in 1856. Tintypes were the American contribution to the process.”

Wet plate collodion has seen a revival in recent years, thanks to a small core of photographers dedicated to exploring the antiquarian art form, Hiott says. “After completing my MFA thesis at Gettysburg, where I spent so much time viewing images from the Civil War, I set out to learn the process, studying with renowned wet plate master John Coffer at his farm in Upstate New York.”

Hiott explains that because it is a photochemical process, wet plate collodion is labor intensive and requires multiple steps to prepare. “Each image is unique because I hand-pour the emulsion before applying light-sensitive chemistry. After making an exposure in camera, I develop the image within a matter of minutes in the studio or in the field, using a portable dark box, as photographers did during the 19th century.”

One of his cameras is a large format – 8 x 10 – wooden box with bellows and Hiott uses antique lenses from the wet plate era. “One of my lenses is 151 years old. It’s a brass barrel Petzval design portrait lens manufactured in 1872 by the Ross company of London. Its visual quality is stunning, creating a sharp plane of focus in the center and an out-of-focus area closer to the edges. Images produced with it seem to swirl. This effect is very characteristic of Petzval design, which did not provide correction for optical distortion,” he adds.

“Slowing down from the digital world, being still, and entering quiet reflection are part of the experience at my studio,” Hiott says. “Exposures are measured in seconds of time, and the average is one to five seconds. It can sometimes take longer depending on the amount of UV light and the age of my chemistry. In my portraits, I want to move beyond surface appearances to more genuine facets of each person’s personality. This is what I want to come through in the finished work – something of that person’s essence. Wet plate collodion is very conducive to the outcome.”

At the end of a portrait session, Hiott’s clients receive one-of-a-kind photographs “and come away with a better appreciation of how much the technology of the medium has evolved. Because my work is grounded in the early history of photography, it invites a conversation between past and present. I enjoy interpreting the modern world with this very old process.”

In addition to his ongoing studio practice, Hiott exhibits regularly in the United States and abroad. After completing his MFA, he began teaching for the Parsons Summer, Pre-College Academy and Continuing Education Program. More recently, he has taught digital photography, alternative processes and art history at several Upstate South Carolina colleges and universities, including Wofford College, Furman University, Anderson University, Spartanburg Methodist College and Greenville Tech.

“In addition to my studio work, I give intensive wet plate collodion workshops, which are available one-to-one and with groups of up to four people. I also teach private Zoom and in-person classes in digital photography and Photoshop,” Hiott adds.

The 40 pieces in the upcoming exhibition will be offered for purchase, with prices ranging from $300 to $1,500.